We need to take a systemic approach to address planetary health challenges and the issues around designing healthy and sustainable cities and communities, understanding that when we make one change we will see other changes in the system.

This was one of the key messages expressed by Professor Tony Capon, from the Sustainable Development Institute at Monash University, Melbourne, Australia, during his keynote talk at the opening session of the 4th Healthy City Design Congress (30 November to 3 December 2020). And it was a message that his fellow keynote speakers, Sir Michael Marmot, Dr David Pencheon and Fiona Howie, also picked up on during the session.

Chaired by Jeremy Myerson, from the Royal College of Art’s Helen Hamlyn Centre for Design, co-organiser of the Congress, the session looked at the issue of recovery, renewal and renaissance through multiple lenses – the climate crisis and current pandemic; the health inequalities angle; the design of our health and healthcare systems; and the planning regime to deliver healthy and sustainable homes and places.

“Resilience means many things,” explained Myerson. “In the narrowest sense, it means snapping back into shape after some adverse impact or effect.”

But cities and governments must do more in the current context, he warned, as simply returning to the old ways is not a path that should be followed. “They must, in a sense, anticipate the future and have the capacity to adapt their health systems accordingly,” he said.

A healthy, fair and green recovery is possible

Indeed, Prof Capon stressed that the old ways had seen incredible progress on improving human health, eradicating and treating certain disease, and in life expectancy, but in “achieving human health gains we’ve exploited the planet at an unprecedented rate, whether it’s increased carbon dioxide emissions, ocean acidification, energy use, global deforestation, water use, fertilizer use – the list goes on”.

In public health, he explained, we often focus on human activities and behaviours that impact our health in positive or negative ways. But there is less attention paid to how human activities affect the health of natural systems, and the flow on impacts for human health from climate change, biodiversity loss, and other ecosystem destruction.

“These are now being called ecological determinants of health,” said Prof Capon.

He went on to outline the Melbourne Experiment, which is bringing together research experts across Monash University to examine key activities and elements of the urban environment before, during and after the Covid-19 shutdown in Melbourne. Areas of research include, among others, changes in energy use during Covid-19; changes in sleep and other behaviours; work changes and health effects; urban air quality and temperature; participation in informal sport; travel patterns during and after Covid-19; and use of open spaces and interaction with natural environments.

“In summary, said Prof Capon, “we need to bring a ‘planetary consciousness’ to health and city design research, training, policy and practice.” This includes the need for an eco-social approach that recognises the ecological, economic and social determinants of health; intergenerational health equity that considers the impact of decisions on future generations; getting better at valuing Indigenous and local knowledge; and systems thinking – acknowledging the interdependence of all species on the planet.

Social justice, health equity and Covid-19

Professor Sir Michael Marmot, director of the UCL Institute of Health Equity, followed Prof Capon by stressing the need not only to “build back better” but to “build back fairer”, highlighting the forthcoming publication of the Covid-19 Marmot Review. This report will look at the societal response to the pandemic on inequalities in society, with the idea of providing long-term recommendations about how to build back fairer; medium-term proposals about addressing inequalities; and arguing what needs to be done immediately.

Describing how the past ten years had amounted to “a lost decade” in regard to tackling health inequalities in England – with evidence showing that the country saw the slowest improvement in health between 2010 and 2020, and the worst record of excess deaths in 2020 among rich nations – Sir Michael stressed that “the health of a country tells us a great deal about how well that society is functioning”.

Describing how the past ten years had amounted to “a lost decade” in regard to tackling health inequalities in England – with evidence showing that the country saw the slowest improvement in health between 2010 and 2020, and the worst record of excess deaths in 2020 among rich nations – Sir Michael stressed that “the health of a country tells us a great deal about how well that society is functioning”.

“The Government had a declaration to roll back the state,” he lamented. “Public expenditure as a proportion of GDP went from 42 per cent on 2009–10 to 35 per cent a decade later. And it was done in a most inequitable fashion.”

The less deprived the area in England, the more likely it is to have no adverse environmental conditions, he explained, and vice versa. “I hope that by bringing together concerns with the climate crisis and concerns with health equity, we can have the building blocks for a fairer society,” he concluded.

Designing safe and sustainable health systems

The fairness angle was taken up by Dr David Pencheon, honorary professor of health and sustainable development at the University of Exeter, who underlined that the climate crisis should be framed as a social justice issue. He added, too, that it is striking how “not only are we stealing from the future but how a very few people are stealing from the future”.

And it’s an issue that the public not only need to get educated about but angry about.

“You still cannot write air pollution as a cause of death on a death certificate, which is a very significant step if we can change that. In London, although we know that we have about 40,000 early deaths across the UK per annum, that number does not have impact. It’s only when we frame it properly as an average eight-month loss of life for every person that it [carries more weight]. If you’re living in London, you need to understand what kind of sacrifices you’re making, and not just get interested but get angry.”

Citing a 2006 paper from Chris Ham, former professor of health policy and management at the University of Birmingham’s health services management centre, Dr Pencheon explained that “unplanned hospital admissions are a sign of system failure”.

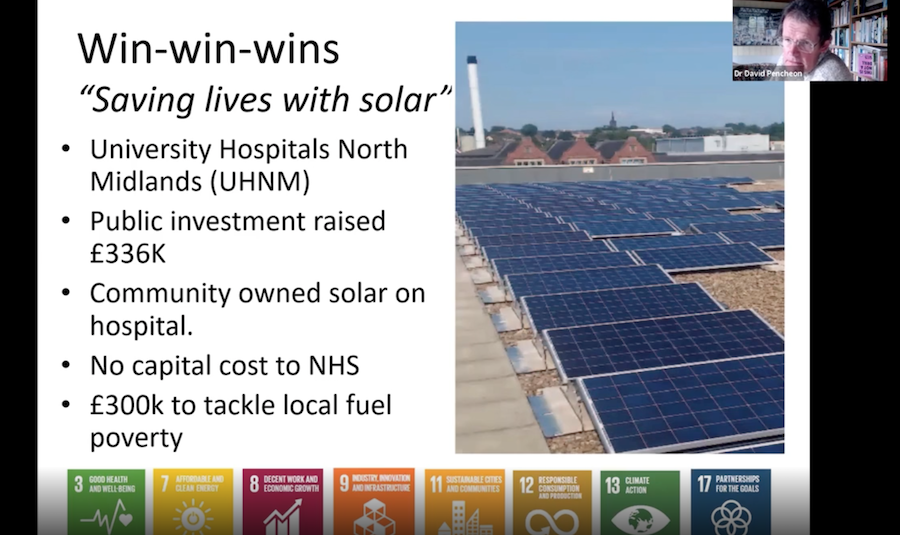

But there are signs of progress, with health systems starting to make a greater contribution to a safe, sustainable, resilient and fair future. They are also recognising their vital community role as anchor organisations.

An anchor mission is a commitment to intentionally apply an institution’s long-term, place-based power and human capital in partnership with the community to mutual long-term benefit. Said Dr Pencheon: “I have a feeling that the healthcare system can reduce inequalities as much by its indirect effect, in terms of employment, partnership and procurement, than it can by its direct effect of making healthcare accessible equally across social classes.”

He concluded: “Let’s focus on systems that improve outcomes, not activity; prevention through partnerships and incentive; new models of care with the default place of care being the home; and empowering staff and patients with IT and near-patient small technology. And healthcare systems and professionals have a huge opportunity in being visible exemplars of a safe and sustainable future.”

Health homes and sustainable places

A similar acknowledgement of the links between housing and health, and the need to unite planning and public health professionals, was expressed by Fiona Howie, chief executive of the Town and Country Planning Association (TCPA).

She described how deregulation of the planning system in England has chipped away at planning controls over the last decade, and much damage was being done through the granting of permitted development rights, which enable offices and light industrial buildings to be turned into homes.

“Through these rights we’ve seen homes as small as 10 square metres,” she said. “We’ve seen homes where the only places for children to play are car parks.”

In trying to reunite the two disciplines of planning and health, Howie highlighted a mixed picture. She pointed out that while national blueprints, such as the National Planning Policy Framework and Planning Policy Wales refer, respectively, to the role of planning in creating healthy, sustainable communities, and the importance of planning in reducing the wider determinants of health and health inequalities, these “warm words” are not always translated into local plans and action.

Worse still, in some cases the planning system is allowing poor-quality, large-scale developments to go ahead. She highlighted the work of the Place Alliance, which earlier this year audited 142 large-scale housing development projects across England against 17 design considerations.

Worse still, in some cases the planning system is allowing poor-quality, large-scale developments to go ahead. She highlighted the work of the Place Alliance, which earlier this year audited 142 large-scale housing development projects across England against 17 design considerations.

“The research concluded that 74 per cent of the schemes were mediocre or poor quality, and that 20 per cent were of such poor quality that they should have been refused planning permission,” said Howie.

She added: “If we are to reduce health inequalities, much more focus is required on the needs of those with the poorest health and greatest needs.”

Sports facilities and cycle routes are important, she explained, but they won’t necessarily be used by those with the poorest health. And simple urban infrastructure such as benches are needed to support people to get active outside by giving them the opportunity to rest.

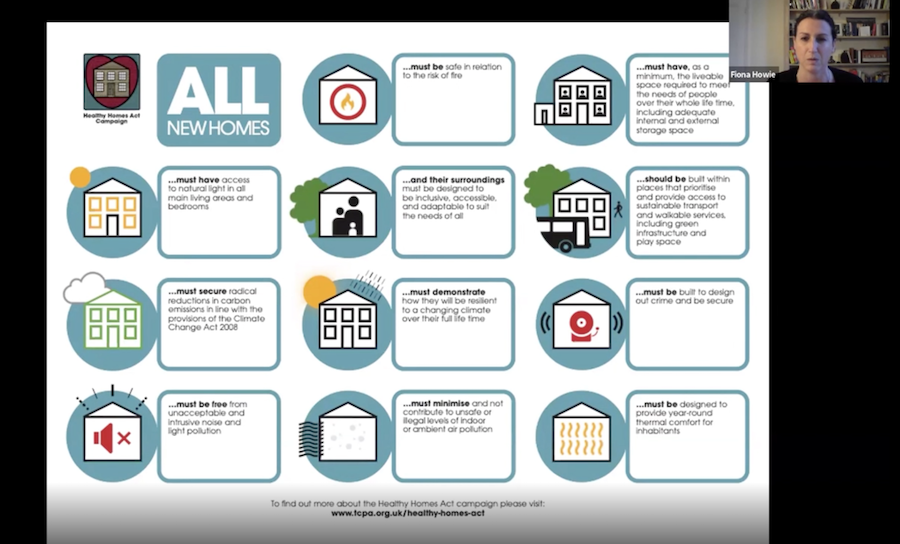

The TCPA is currently campaigning for new primary legislation to implement a coherent set of changes delivered through amendments to building regulations and policy. Its Healthy Homes Act not only focuses on individual homes, such as ensuring access to natural light, and being free from noise pollution and air pollution, but it also recognises wider placemaking principles, such as the importance of green spaces and play areas.

“The planning system has the potential to be really important in tackling lots of the issues around health, health inequalities, the wider determinants of health, and climate change,” concluded Howie. “Our homes and where we live are incredibly important to our health and wellbeing.”